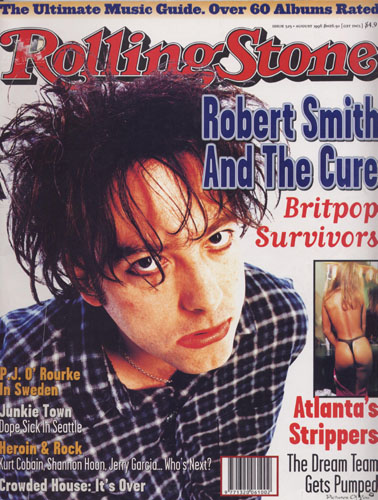

"Lipstick Traces : Robert Smith and The Cure" (text Below)

August 1996 - Rolling Stone (Australia)

"Lipstick Traces : Robert Smith and The Cure" (text

Below)

I think that was a turning point, that one, says Robert Smith, as the last notes of Jupiter Crash fade out. He looks around at the rest of his band for moral support. I hope so, anyway.

It's June and the first of two sold-out nights at London's cavernous Earl's Court Arena, and The Cure have been stuck in second gear for the better part of an hour. Smith, clad somewhat incongruously in a USSR ice hockey shirt, has so far apologized three or four times for various aspects of the band's performance - his singing, the hiccupping light show and, rather unnecessarily, for his failure to think of anything interesting to say between songs. It hasn't been a good night, and it doesn't go on to improve much. The light show is cool when it works, but you don't go to a Cure concert expecting to find you and your companion discussing the light show, especially not during songs. As I join the appreciable portion of the crowd who have measured the prospect of encores against last orders in the West End and found the former option wanting, it seems there are two ways of looking at it. One is to say fair play to the Cure for still being haphazardly human enough to miss the occasional open goal. After all, after almost 20 years of existence, most stadium-sized bands have got their act so refined and rigidly organized that they could play it in their sleep, and very often do. You can bet The Cure will, at some point in their tour - tonight's grim performance notwithstanding - turn in a performance of transcendent passion and nerve, will seize what Smith calls one of our occasional moments, when we can be something really precious. The other is to wonder, as local reviews of concerts and of the new album, Wild Mood Swings, all have, if maybe, for the first time in two amazing decades whether The Cure are edging towards redundancy; if we still need them. It's a reasonable point to ponder; Robert Smith certainly has.

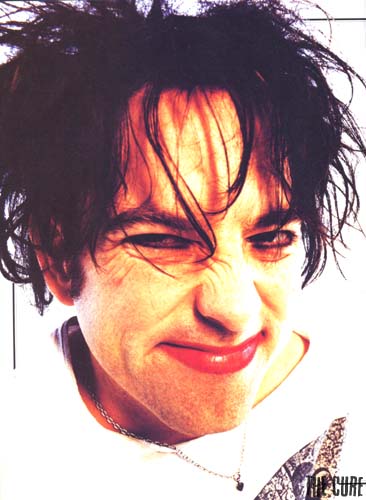

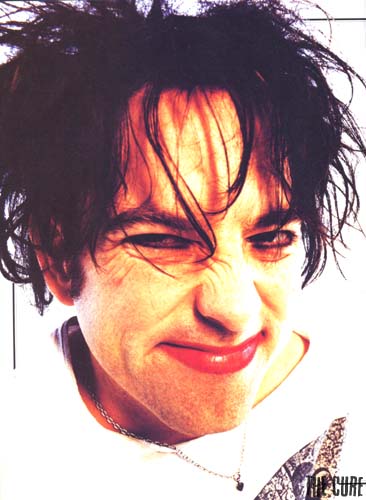

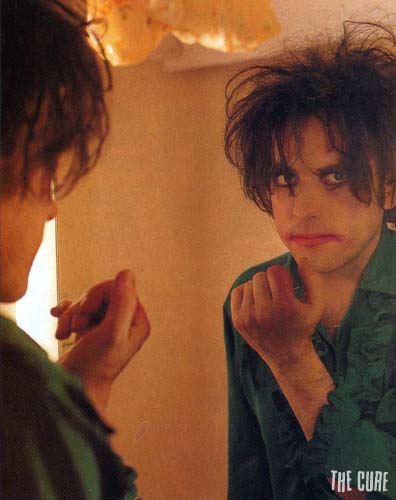

Four weeks before the Earl's Court show, and three days after his 37th birthday, Robert Smith swallows two Nurofen with his coffee and apologizes again for his hung-over demeanor. It's not that he had too much to drink last night, rather that he had to get up ridiculously early, at half-past nine or something like that! to be here. "Here" is a cell-like dressing room at BBC-TV's complex in London's unlovely White City, a suburb that boasts the home ground of Smith's beloved Queen's Park Rangers, who have just crowned a diabolical season by falling from the top division of football. I'd be grateful it we could leave QPR out of this, says Smith with a heartfelt sigh. I've hardly started doing promotional stuff for this record, and I'm already tired of gloating journalists. Later today, the Cure will record a live performance for the late night music program hosted by former Squeeze keyboardist Jools Holland, sharing an unlikely bill with Tasmin Archer, Mark Morrison and Willie Nelson. Regrettably, no duet will be attempted. Smith, in the meantime, contemplates the view outside the window - a sculpture of the sort admired by batty communist dictators and people who pretend to like industrial art. It's been four years since Wish, and two since being in the Cure was a full-time occupation. I attempted sculpture at one point, he says, peering into the courtyard outside. I got a block of Bath stone, and made a head. It proved to be harder work than I thought it would be. It was the inner head, you understand. It ended up being a very Tony Hancock experience. I only got half of it done, but it looks alright in profile. Eventually, I left it in the garden covered in live yoghurt so mould would grow over it then it would be, like, you know, real art. It looks bloody awful. Smith seems the same as ever, tripping over his ill-fitting boots and blinking beneath his perpetually riotous hair. He also remains an endearingly uncertain interview subject, ambling off at tangents, restraining himself from excessive auto-analysis with a deadpan humility unusual for someone in his position. Since the 1978 release of their first single, a punk-rock rewrite of Albert Camus' The Outsider, called Killing an Arab, the Cure have sold more than 2.3 million albums, and Smith's haphazardly made-up face has long since transcended mere fame to become genuinely iconic. Probably fairly tactlessly, I mutter something about David Bowie, who recently ventured from the audio to visual arts with the approximate surefootedness of a three-legged hound. Oh no, no, says Smith, horrified. I'm not deluded enough to think that just because I've done something, it's good. I do have this streak of perfectionism, and I still feel like music is the only area I get even close.

The release of Wild Mood Swings, The Cure's tenth studio album, ends three relatively quiet years for Smith. After the world tour that accompanied The Cure's last album, Wish, ended in 1992, Smith took it upon himself to edit and mix a Cure concert film, Show, hoping that the experience would serve as a crash course in film making. The results were not quite what he expected. It was interesting for the first couple of weeks, he recalls, but I gradually grew to loathe everything about myself and the group. At the time, I was going fairly insane because I hadn't had a break from the group for a couple of years, and I couldn't get the image of the group out of my head. I started dreaming about the bloody thing, and every waking moment was consumed with agonizing over edits and angles and things. I think I realized then that I needed a break. Nonetheless, Smith persevered, mixing the Show and Paris live albums, until about April 1993 when his wires finally came loose. I'd started to feel like I was more real on the film than I was in real life, when I was editing it. I got to the stage of turning it off and laughing triumphantly, saying 'Ha, that'll show you who's in charge.' I was drinking a lot of course. Well, this would hardly be a Cure piece if somebody wasn't. Smith continues: I mean it's not like I thought I'd never do another gig, because I've said so many times now that I don't take it seriously myself. I went over to New York without the group, and spent a few weeks there because I hadn't done anything without the band for two years, which is pretty weird, normally being in the position where anything I decide to do always has repercussions for other people. But it was quite a liberating thing, being able to lie in bed for a couple of extra hours if I felt like it, or hiring a car and driving out of New York. Also, I had the thing with Lol to think about. There's a long silence in which Smith grows perceptibly gloomy. When he talks about the legal wrangle with Lol Tolhurst, who co-founded The Cure, was once Smith's best friend, and who followed his acrimonious departure from the band with a lawsuit alleging various financial inequities, Smith sounds like the victim of an especially cruel and pointless practical joke. I didn't realize how much that had affected me until after it had been and gone, and I realized that it really helped to contribute to my...well, whatever. I couldn't win; all I could hope for was to walk away in exactly the same position I'd been in, but without a court case hanging over me. Whereas he stood to win a lot, like the right to use the Cure's name for his own purposes, and that's why I fought the case. The rest of it was just bollocks. I wouldn't have bothered with the rest of it because it wasn't worth my time, energy or money. Want, the first song on Wild Mood Swings, laments, However hard I want / I know deep down inside / I'll never get more than I hope / Or any more time. An outraged railing at the relentlessness of time's march has been a favourite Cure motif. Smith, never comfortable with glib analyses, assembles a disdainful expression, but acknowledges a connection. I did have a burst of writing after the case. But it was horrendously time consuming, especially as I don't live in London - I live in Sussex - and to have to travel three times a week for those meetings, which always started at eight or nine in the morning, that's what made me angry, and having to spend all these dull, dusty hours trawling through contracts. It was a bit draining, I tried to adopt a sort of zen attitude to it, use the time positively, but ultimately it was just a waste of four months of my life - that's what I'm still angry about.

Wild Mood Swings is not a great Cure record like Head on the Door or Disintegration were great Cure records. Nor is it a deranged, distorted, barely endurable but perversely compelling Cure record like Pornography or Faith. It's a pretty good record like Wish and The Top were good records. If it was a debut album, says Smith, people would be going mad over it, and he's right. Smith also says something else , which has the same effect on the conversation as jamming a crowbar into the spokes of a trundling bicycle. What do you think its weaknesses are? There is no sensible answer to this. For a start, Robert Smith is quite a big bloke, and he's between me and the door. Beyond that is the undeniable okay/not bad/pretty good answer. Wild Mood Swings has its moments, certainly. Return and Mint Car are both lovely, expertly executed pop confections which find Smith defiantly playing up to all his clichés. The 13th, the first single, is a silly but irresistible mariachi meltdown. Bare, the closing track, is one of the most overpoweringly bereft things the band has ever recorded, which is saying something. Then there's Club America and Round and Round and Round - songs about being in a rock and roll band - which are never the sign of a muse firing on all cylinders.

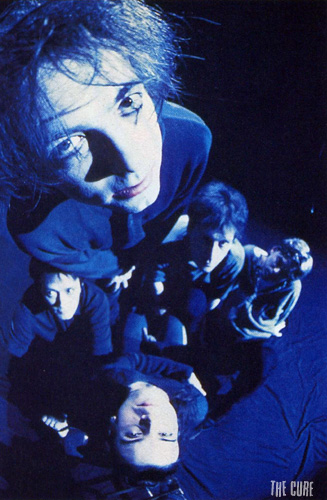

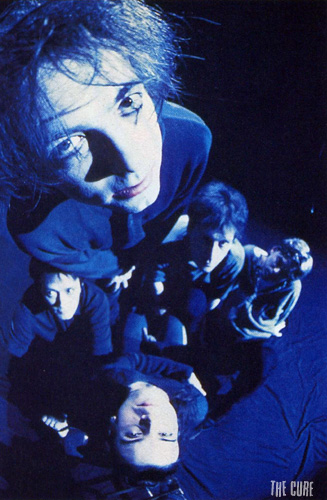

I eventually mumble that it's the thing about how he's been away for four years and come back with what is, well, another Cure album. And I've already got twelve. Mmmm, says Smith, clearly non-plussed by this improvised critique. To me, though, the Cure isn't a linear event. There have been several distinct group line-ups. In my own mind, there have been five very different groups called the Cure, and I have been in all of them. The Cure that Smith is in now is a comfortable blend of youth and experience. After the global Wish tour, long time guitarist (and Smith's brother-in-law) Porl Thompson quit the band pleading tour fatigue. Less expectedly, drummer Boris Williams handed in his cards to go and see the world. There was even a brief period where the bass player Simon Gallup left, and the Cure were down to Smith and roadie-turned-keyboardist Perry Bamonte. Apparently unfazed, Smith went off and hung around in New York and Paris, listened to a lot of Mahler and a distressing amount of opera, reintroduced himself to a formidable clan of 17 nephews and nieces, dabbled in amateur astronomy, grew a moustache, thought better of it, and began to do sensible, grown-up things like attend community meetings in his home town. When the time finally seemed right for the Cure to reconvene, they did so with the panache that might be expected of a band who circumvent their singer's terror of flying by sailing to and from America in the QE II. Gallup decided not to quit after all, Disintegration-era keyboardist Roger O'Donnell was recalled from exile in Toronto, and a classified advertisement in Melody Maker recruited drummer Jason Cooper, who had been playing with My Life Story, a gloriously excessive big-band concern shortly to be famous in their own right. Rather than submit themselves to the austerity of the studio, the Cure had the bright idea of renting Jane Seymour's country estate for the year, determining to make an album by the time the lease was up. It was brilliant, says Smith, smiling, the best year of my life.

If Wild Mood Swings does sound like anything, it sounds like people enjoying themselves. Smith, especially, is having a riot, turning himself into the victim of a fan's obsessions on Strange Attraction (A true story, he confirms), experimenting with singing voices other than his patent wracked whine and, oddly, for a long and happily married man, tearing holes in the idea of monogamy. "This is a Lie is the first song that Mary ever asked me seriously about, says Smith, before continuing slowly, terrified of appearing pompous. The presumption that everything I write is equally heartfelt is one that shouldn't be made. On albums two, three and four, and to a lesser extent, Disintegration, everything I wrote was an expression of extreme emotion. I used to think that if a song wasn't wrenched screaming from the inside then it wasn't valid, but now I think the only way that I can develop as a songwriter is by entertaining people. I can approach a subject from a point of view that I wouldn't necessarily hold. That's part of the fun, having developed over the years a persona that allows me to get away from things. At the suggestion that it might also be a part of growing up, or growing old, he flinches, smiles and shrugs. I think in the past I've really packed things in, perhaps with an unspoken fear of death, but it's a weird paradox because the more you pack in the more you do, and the more likely you are to cop it. But at the end of it all, you're still here, and there is a real temptation to sit back, rather than raging against the dying of the light. I do feel really comfortable at home, but I want to remain on edge, so I feel slightly guilty about it. I don't have to do anything, which is wonderful, it's all I've ever wanted, but it can be incredibly frightening."

It's intimidating, limitless opportunity.

But part of it is also growing up, and maturing, I'm much less uptight about everything to do with me, really, but also angrier about things that are going on in the world and social issues. However, there's no chance he'll sing about them : The Cure quietly support worthy causes, Smith says. I like the idea of The Cure being a pop group, because I don't want to be a serious artist. One day, I might turn into one and do something that is a testament to my life. What I do with The Cure is sometimes brilliant, and a lot of it is average; it's not earth-shattering and I have no illusions that it is. I don't think you can be a serious artist in a pop group, and I don't want to be one because I don't feel I need that kind of respect.

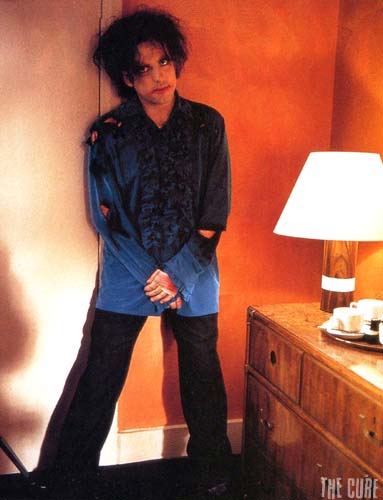

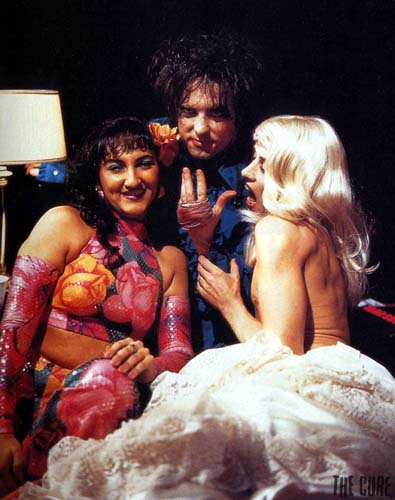

And with that, Robert Smith gets up to put on his make-up before wandering off in his blue ruffled shirt to perform The 13th, a song about a stripper, accompanied by a brass section and a leopard skin clad backing singer. Willie Nelson looks on, bemused, from the other side of the studio.