"THE CURE - DID IT AGAIN - The Last Goodbye"

July, 2004 -

Les Inrockuptibles (Argentina)*

(Translation below)

"THE

CURE - DID IT AGAIN - The Last Goodbye"

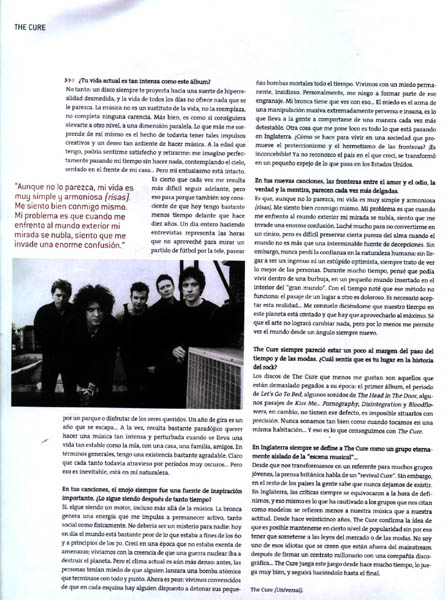

THE CURE - DID IT AGAIN

They’ll come to Argentina, they won’t. They’ll split up, they won’t. Between more And more rumors, Robert Smith and his band present their best album in years. Exclusive interview.

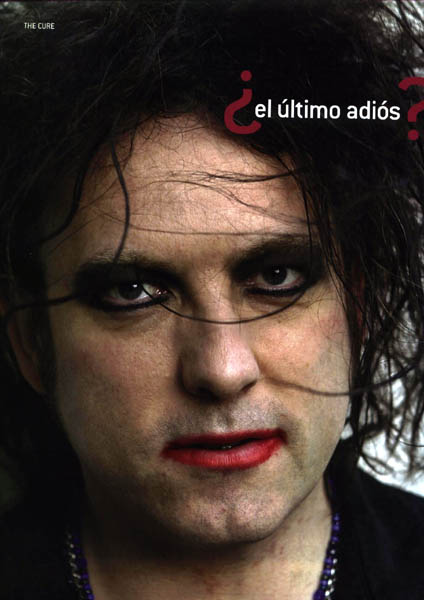

The last goodbye?

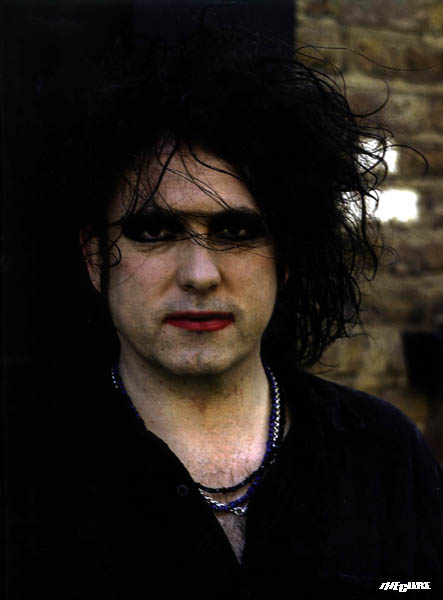

Since early 80’s, Robert Smith is being announcing every The Cure album as if it was the last. However, this time the threatening seems to be for real. Twenty five years after their debut, in the middle of the 80’s revival fever and with its discography in the most contemporary interesting groups horizon –from The Rapture to Interpol-, the everlasting pop black angel returns to put his band in movement with the ambitious balance album The Cure, their new work. Towards rumors of their return to Argentina, an exclusive interview with the responsible of a myth that resists from disappearing.

Last month, Morrissey returned from the darkness rescued by Jerry Finn, a young Californian punk rock producer who had learned, by working with exalted bands such as Blink 182 and Green Day, up to which point the English singer is being considerate a legend. Robert Smith, another 80’s leader, discovered through another producer of this generation, Ross Robinson, up to which point his often clients (At The Drive-In, Slipknot, Korn…) worshiped the The Cure albums. In fact, very few has been said about the legacy of The Cure in the past 20 years compared to what has been said during the year 2004: from The Rapture to Interpol, a whole generation of young people enjoys their pleasant visit to the fashionable 80’s decade to discover authentic master pieces like Seventeen Seconds (1980) or Pornography (82). Two albums that, watched from the distance, are useful to realize that, in matter of neurology rock and suffocating psychedelic, no one ever went so far before.

But instead of drilling insensitively, in a New Order style, this rehabilitation massive wave, Robert Smith went back to the recording studio with strengthen wish and faith. Far from the boredom and the routine, his new album surprises for its renewed tension, its ambitions and intensity. Like a beautiful summary of a band that tried it all, The Cure can have fun like this with a charming pop, strengthen with a gloomy rock or slip away in a psychedelic labyrinth. As if, under the (supposed) excuse of concluding with dignity his career, Smith and his people would have chosen to make an inventory of all their possible incarnations.

The Cure: a title in terms of conclusion after twenty five years of trajectory, now visited again under all its shapes. Because only the pop commander Robert Smith knows if his dark submarine will continue going on through the darkest and most refreshing rock waters of all times after their supposed last album.

Lets take-leave from them just in case… Goodbye, The Cure. Goodbye. And thanks for everything.

JD Beauvallet

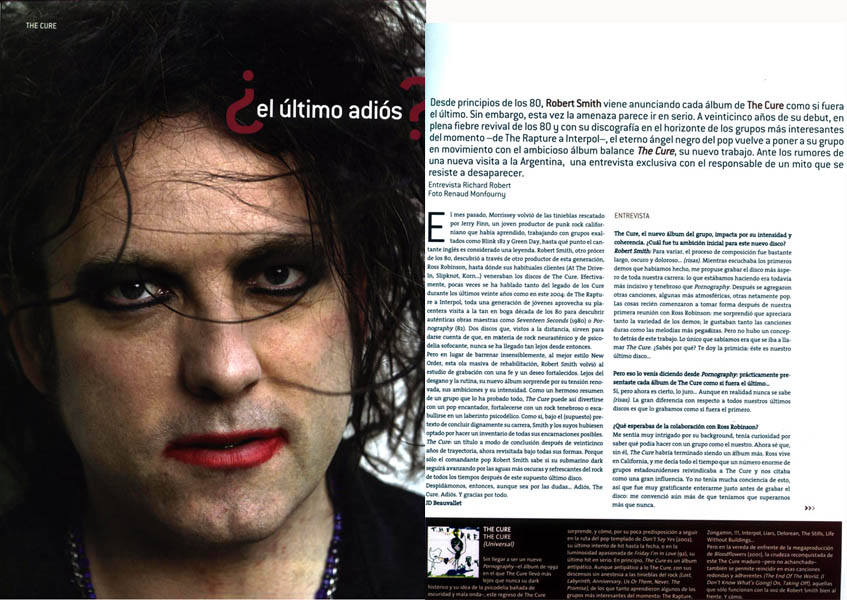

INTERVIEW

The Cure, the new band album, makes an impact with its intensity and coherence. Which was your initial ambition for this new album?

Robert Smith: For a change, the composition process was pretty long, dark and obscure… (laughs). While I heard the first demos we did, I decided to record the roughest album of our career: what we were doing was even more incisive and gloomy than Pornography. Then other songs were added, some more atmospheric, others exclusively pop. Things started to have shape after our first meeting with Ross Robinson: I was surprised of his appreciation for the variety of the demos; he liked from the roughest songs to the more sticky melodies. But there was no concept behind this work. The only thing we new is that it was going to be called The Cure. You know why? I’ll give you the first fruit: this is our last album…

But you’ve been saying that since Pornography: you practically presented every The Cure album as if it was the last one…

Yes, but now it’s for real, I swear… although you never know (laughs). The big difference with all our last records is that we recorded it as if it was the first.

What did you hope for Ross Robinson’s collaboration?

I felt very intrigued by his background, I was curious to know what he could do with a band like ours. Now I know that, without him, The Cure would have ended being just one more album. Ross lives in California, and kept telling me that a huge group of American bands were revindicating The Cure and quoted us as a big influence. I wasn’t really aware of this, so it was very pleasant to know right before recording the album: he convinced me even more that we should improve ourselves more than ever.

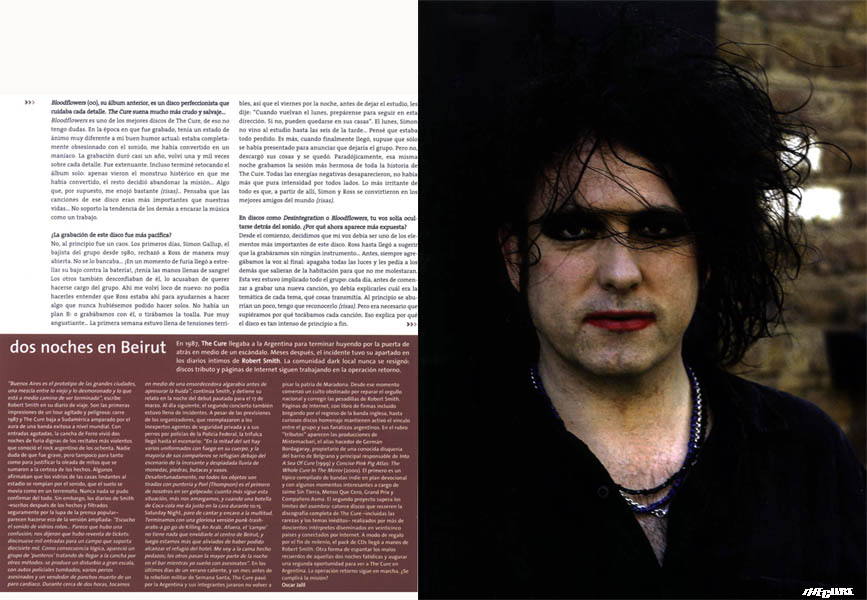

Bloodflowers (00), your previous album, is a perfectionist album that watches out each detail. The Cure sounds much more hard and wild…

Bloodflowers is one of the best The Cure’s albums, I have no doubt about this. By the time it was recorded, I was in a mood a lot different from my current good mood: I was completely obsessed with the sound, I was turned into a maniac. The recording lasted almost a year, I went back again and again on every detail. It was exhausting. I even ended up retouching the album by myself: as soon as the rest saw the hysterical monster I became they decided to abandon the mission… thing that, of course, made me very angry (laughs)… I thought that the songs of that album were more important than our lives… I can’t stand the tendency of others to face music as a job.

The recording of this album was more pacific?

No, at the beginning it was a mess. The first days, Simon Gallup, bass since 1980 (late 1979), rejected Ross in a very open way. He couldn’t stand him… In an angry moment he got to smash his bass towards the drums! His hands were bleeding!. The others didn’t trust him either, they accused him of trying to take possession of the band. At that moment I went mad again: I couldn’t make them understand that Ross was there to help us doing something that we could have never done by our own. There was no ‘B’ plan: either we recorded with him, or throw the towel away. It was very distressed… The first week was full of terrible tensions, so on Friday night, before leaving the studio, I told them: “when you come back on Monday, prepare to continue on this direction, or stay home”. On Monday, Simon didn’t come to the studio until six in the afternoon… I thought everything was lost. In fact, when he finally showed up, I thought he went to announce he was leaving the band. But he didn’t, he discharged his things and stayed. Paradoxically, that night we recorded the most beautiful session of all The Cure history. All the negative energies disappeared, there was nothing more than pure intensity everywhere. The most irritating thing is that, from then on, Simon and Ross became the best friends of the world (laughs).

In albums like Disintegration and Bloodflowers, your voice used to hide behind the sound, why does it appear more exposed now?

From the beginning, we decided that my voice should be one of the most important elements of this album. Ross even suggested recording it with no instruments… Before, we always used to add the voice at the end: I turned all the lights off and asked everyone to leave the room so they wouldn’t disturb me. This time all the band was implicated: every day, before recording a new song, I had to explain them the theme of each song, which things it transmitted. At the begging they were a bit bored, I have to recognize that (laughs). But it was necessary that we knew the reason why we were playing each song. That explains why the album is so intense from beginning to end.

Your current life is as intense as this album?

Not that much: an album always projects you towards some kind of immeasurable reality, and every day’s life doesn’t offer something like this. Music is not a life substitute, it doesn’t replace it, and it doesn’t fulfill any lack. It kind of takes you to another level, to a parallel dimension. What most surprises me is the fact of still having such creative impulses and a burning desire to make music. At my age, I could feel satisfied and retire: I can perfectly well imagine myself spending my time doing nothing, staring at the sky, sitting in the front of my house… But my enthusiasm is intact. It’s true that every time is more and more difficult for me to move forward, but that also happens because I’m conscious that now I have much less time ahead than ten years ago. A whole day doing interviews represents the hours I didn’t spent watching a soccer match on TV, walk on a park or enjoy my love ones. A year touring is a year that slips away… At the same time, it turns to be very paradoxical willing to make such intense and perturbed music when you have a stable life as mine’s, with a house, a family, and friends. In general terms, I have a pretty nice existence. Of course I still go through very dark periods from time to time… But that’s inevitable, it’s in my nature.

In your songs, anger was always a very important source of inspiration. It still is after such a long time?

Yes, it’s still a starter, even beyond music. The row generates an energy that drives me to keep active, both socially and physically. It shouldn’t be a mystery for anyone: nowadays the world is much worst than it was in the latest sixties and early seventies. I grew in times that weren’t free from threatening; we lived with the belief that a nuclear war was going to destroy the planet. But today’s reality is much heavier: before, people were afraid that somebody could drop an atomic bomb that finished with everything. Now is worst: we live convinced that in every corner there’s someone willing to detonate his little lethal bombs all the time. We live with a permanent fear, insidious. Personally, I refuse to be a part of that engineering. My row has to do with that… Fear is a massive manipulation weapon extremely perverse and insane, it makes people behave in a detestable way. Another thing that turns me crazy is the situation in England. How can we live in a society that promotes protectionism? It’s unthinkable! I can’t recognize any more the country I grew up in, it turned in a small mirror of what is happening in the United States.

In your new songs, the frontiers between love and hate, truth and lie, seems thinner.

Is that, even if it doesn’t seem, my life is very simple and harmonious (laughs). I feel good with myself. The problem is that when I confront the outside world, my sight becomes cloudy, I feel invaded by a huge confusion. I fought very hard for not becoming a cynic, but it’s hard to preserve some purity in the soul when the world is an everlasting source of deceptions. Nevertheless, I never stopped trusting the human nature: without being naïf or a stupid optimist, I always try to see the best side of people. During a long time, I thought I could live inside a bubble, in a small world inside the “big world”. With time I realized that that method doesn’t work out: the path from one to the other is painful. It’s necessary to accept this reality… I console myself saying that our time in this planet is limited and we have to take the best advantage of it. I know art won’t ever change anything, but at least it allows me to see the world from a different angle.

The Cure always seemed to escape from the pass of time and fashions. Which one do you think is your place in rock history?

The The Cure albums I less like are those that are too stuck to their epoch: the first album, the Let’s go to bed period, some sounds from The Head on the Door, some passages of Kiss me… Pornography, Disintegration and Bloodflowers, on the other hand, don’t have this defect, it’s impossible to situate them precisely. We never sounded so well as when we played in the same room… And that’s what we achieved with The Cure.

In England The Cure is defined as an always isolated from the “musical scenery” band…

Since we became a referent for many young bands, British press talks about a “Cure revival”. However, in the rest of the countries people know we never stopped existing. In England, the critics were always wrong when trying to define us, and that’s exactly what captivates the bands that take us as their referents: they refer less to our music than to our attitude. For twenty five years, The Cure confirms the idea that it is possible to maintain a certain level of popularity without having to submit to market or fashion rules. I’m not one of those idiots that believe they’re out of the mainstream after signing a millionaire contract with a record company… The Cure plays this game since a long time ago, and plays it fine, and will keep on doing so until the end.

Two nights in Beirut

In 1987, The Cure arrived to Argentina to escape through the backdoor in the middle of a scandal. Months later, the incident had its chapter in Robert Smith’s personal diary. The dark local community never resigned: tribute discs and web pages keep on working in the ‘return’ mission.

“Buenos Aires is a prototype of the big cities, a mixed up between the old and torn and what is in half way to be completed”, Robert Smith writes in his travel diary. These are the first impressions from an agitated and danger tour: it’s 1987 and The Cure comes down to South America followed by a world level successful band aura. With sold out tickets, Ferro’s stadium lived two nights of fury worthy of the most violent recitals that the argentine rock new during the eighties. Nobody doubts that it was serious, but not as much as to justify the wave of myths that were added to the truth of the facts. Some say that the glasses of the houses next to the stadium broke because of the sound, that the ground moved as if it were an earthquake. Nothing was ever really confirmed. However, Smith’s diaries –written by him after the facts and surely filtrated by the popular press magnifying glass- seemed to become echo of the enlarged version: “I hear the sound of broken glasses… It seems that there has been a confusion; they told us that there has been ticket resale: nineteen thousand tickets for a stadium that supports seventeen thousand. As a logic consequence, a group of ‘punchers’ appeared trying to get to the field by other methods: a big scale disturb is produced, with tumbled police cars, several dogs murdered and a hot dog sales man dead from a heart attack. During almost two hours, we played in the middle of a deafening jabber before hurrying the leave”, Smith continues, and stops his story in the debut night pact for March 17th 1987. The following day, the second concert was also full of incidents. Despite the organizers precautions, who replaced the inexpert private security agents and their dogs by Federal Police men, the squabble reached the scenario: “In the middle of the set there are some uniformed men with fire in their bodies, and the majority of their companions sheltered under the scenario from the incessant and pitiless rain of coins, rocks, armchairs and glasses. Unfortunately, not all the objects were thrown with aim and Porl (Thompson) is the first one of us being hit: the more that situation persisted, the more we bitter up, and when a Coke bottle hits me right in the face during 10:15 Saturday Night, I stop singing and face the crowd. We finished with a glorious version of punk-trash-a go go from Killing an Arab. Outside, the ‘field’ has nothing to envy downtown Beirut, and then we are more than relieved to reach the shelter of the hotel. I go to bed in pieces; the others spend most part of the night at the bar while I dream with murders”. In the last days of a hot summer, and a month before the Holly Week military reveal, The Cure made its pass through Argentina and their members swear to never step Maradona’s mother country again. From that moment on, an obstinate cult started in order to repair the national proud and mend Robert Smith’s nightmares.

Web pages, with sign book included pleading for the British band return, even

curious tribute albums maintain active the bond between the group and the

Argentine fans. In the section “tribute” appear Mistemacbari productions, the

alias maker of Germán Bordagaray, owner of a well known record store of Belgrano

city and main responsible of Into a Sea Of Cure (1999) and Concise

Pink Pig Atlas: The Whole Cure in the Mirror (2000). The first one is a

typical bands compilation in devotional plan and with some interesting moments

by Jaime Sin Tierra, Menos Que Cero, Grand Prix and Compañero Asma. The second

project excels the amazement limits: fourteen disks that go through the complete

The Cure discography –including rarities and unpublished tracks- done by more

than two hundred interpreters disseminated in twenty five countries and

connected through internet. As an end of the century present, the CD’s pack got

to Robert Smith hands. Another way of scaring away the memories of those two

fateful nights, and wish for a second opportunity to see The Cure in Argentina.

The ‘return’ mission is still running, will it be accom.

Thanks so much SABRINA for TRANSLATING!!!

and thanks DAYNA for getting me a copy of this magazine.!!